The beginning

Every morning in the fall of 1997 I would wake up at 6AM and immediately jump out of bed. I went straight to my Fujitsu laptop in the home office, leaving my then-girlfriend sleeping in the bedroom. I didn’t have anywhere to be; nobody was paying me, and this wasn’t for a class. I was working on a new project: a sign-language synthesis prototype.

This project was the culmination of several threads in my life. I had been inspired to go back to grad school by spending time talking about language with my girlfriend, a linguist who had just earned her PhD. For the past two years I had been making my living in information technology, working my way up from Microsoft Office trainer to LAN operations tech. I had also been taking night classes at the American Sign Language Institute and participating in discussions on SLLING-L, a sign linguistics email list, and the SignWriting List.

I had chosen the linguistics doctoral program at the University of New Mexico because I knew it was strong in sign linguistics, and I had just arrived in August. I was taking a course in psycholinguistics with the sign linguist Jill Morford, and a course in ASL.

Several people had asked me, “So you’re interested in language, and you’re interested in computers. Is there a way you could combine these interests?” I replied, “Well, there’s speech synthesis,” but that technology was already pretty well established. I realized that there wasn’t much in the area of technology for sign languages. What would sign synthesis look like?

When I arrived in Albuquerque I mentioned this idea to Sean Burke, a linguist and programmer I had made friends with on an earlier visit. Sean suggested using Virtual Reality Modeling Language, a standard for describing three-dimensional objects and their movements. People could install a plugin in their web browsers, and point it to a VRML (since renamed Web3D) site, and the plugin would display the 3D animation.

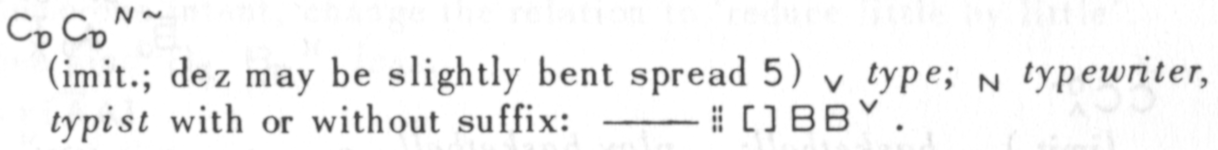

I followed Sean’s tip and discovered that there was a standard for specifying and animating humanoids in VRML, and a way to control the plugin through Javascript. I created a basic animation of a sign using Javascript, but after numerous frustrations I concluded that it was best to assemble the VRML through a custom Perl templating system controlled by CGI forms.

Getting the word out

Once my system was working to the point that it could create intelligible signs, I showed it to the faculty and students who were studying sign languages. The strongest interest came from Jill Morford, my psycholinguistics professor, who recognized that I had created a sign-language analog of the early speech synthesizers that were used at Haskins Labs to demonstrate the categorical nature of speech perception and its acquisition in language learners.

Jill realized that my system, which I had dubbed SignSynth, could be used to test whether perception of sign languages is similarly categorical, and how it is acquired. The following year she obtained a grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the question, and included some money to support me part time and get an office that I shared with a couple other students.

Around that time I had a meeting with my Committee on Studies. They liked my work, but told me that simply creating a sign synthesis system wasn’t theoretical enough for a Linguistics dissertation. If I used it, I would have to use it to demonstrate an answer to some theoretical question.

Doubts

That year I also took a course in literacy education called Teaching Reading to the ESL Student. The professor, Leila Flores-Dueñas, was happy to support me applying these lessons to Deaf students, but throughout the course she stressed the importance of grounding our teaching in the priorities of our students, and orienting our research to the goals of the populations we were studying. She pointed out further that we should be working to help lift up people who were oppressed or disadvantaged, so when we are working with people in those situations we have a particular obligation to fit our work to their priorities.

I realized that the same principle applied to developing applications: an app that touches disadvantaged people should help them to fulfill their goals. This brought back to mind the fact that I had never seen a Deaf person ask for a sign synthesis or natural language processing application.

I actually hadn’t talked much with Deaf people about language technology. This was in part because there is a general suspicion of hearing people in Deaf communities, particularly of hearing people who come bearing language technology. The suspicion is well earned; check out what Deaf people have to say about Alexander Graham Bell.

I had difficulty overcoming this suspicion because I had only been studying American Sign Language for a few years. I could communicate with Deaf people, but only if they were patient, and many of them had no reason to be patient with some random hearing person. I realized that I didn’t necessarily have any technology that could help them accomplish their goals, and if i did, they weren’t necessarily going to try it.

Challenges

That year I ran into two major challenges in sign synthesis, both relating to the placement of hands in space. The higher-level challenge relates to signs that are called depicting or iconic verbs, or classifier predicates. In these signs, the relative location, orientation and movement of the signer’s hands are used to refer to a similar spatial relationship or movement. In a classic example, an ASL signer can depict the movement of a car by making the “3” vehicle classifier shape with one hand and moving that hand in a scaled-down version of the car’s movements.

Iconic verbs are very difficult to specify in a user interface, because the level of detail of the location and movement is only constrained by the signer’s control of their hands, and the audience’s visual perception abilities. Specifying, representing and transmitting such signs is, at a minimum, a vastly different task than that for lexical signs, where there is a relatively small set of locations and movements.

The lower-level challenge involved figuring out how to bend the shoulder, elbow and wrist on a humanoid figure so that the figure’s hand winds up in a particular place, facing in a particular direction. This is a well-known problem, called inverse kinematics, that we humans solve intuitively every time we make a gesture or pick up an object.

There are computer libraries for inverse kinematics, and I tried to connect my animation code to those libraries, but they were written in C++, not Perl, and after several months I still hadn’t figured it out.

I described these challenges of inverse kinematics and representing classifier predicates to my committee, but they did not consider them to be theoretical enough for a dissertation. I was able to create the videos for Jill Morford’s categorical perception experiments, and she suggested that I could study categorical perception for my dissertation. In retrospect I should maybe have taken her up on it, but instead I decided to study a cosmopolitan, largely privileged community where the speakers were all long dead: the history of Parisian French through theater.

Legacy

My papers on SignSynth are routinely cited as one of the pioneering works in text-to-sign, mostly by developers who didn’t have a Professor Flores-Dueñas to teach them the importance of serving the language community, and who don’t follow my lead in separating synthesis from translation.

The paper that Jill Morford wrote with me and my fellow students about categorical perception has also had lasting influence; we failed to find a strong effect of categorical perception to match those found in speech, and the implications of that are still being discussed.

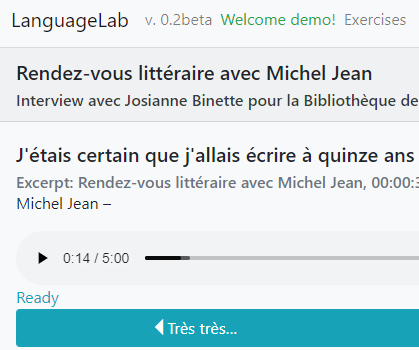

I never wanted to commercialize SignSynth, knowing that average incomes for Deaf people tend to be significantly lower than the general population, so I made it publicly available as a web application. The original application relied on third-party browser plugins to display the VRML, but over time, web browser makers dropped support for those plugins.

In 2022 I rewrote SignSynth from scratch in Javascript, using a relatively new 3D graphics library, Three.js, and made the code available on GitHub. I updated the interface to follow “character pickers” like Richard Ishida’s IPA Character Picker, replacing the old interface that was heavy on drop-down menus. I also created a standalone character picker for the Stokoe notation that it used for the original text.

What SignSynth meant to me

Thinking back to 1997, what got me so excited, what inspired me to move across the country and start a doctoral program with no promise of funding, living off of part time jobs and student loans, and spend so many unpaid hours every day, was the idea that I was creating something new, something that could be useful to people.

When I was young, I admired inventors, both real-life inventors like Thomas Edison and fictional ones like Professor Bullfinch from the Danny Dunn books. My father, my stepfather and my mother’s boyfriends in between were all tinkerers, and they made useful things. I didn’t have money to buy a lot of tools and equipment, or space to keep it in, but I did have access to computers, and the skills to program them.

Looking back, there was some ego in this. Why was it important for me to make these things, and not someone else? Why not be satisfied fixing the Novell servers for Chase Manhattan, or even sending faxes for John Hancock?

To be fair to myself, I have never been a competitive inventor. While I was working on SignSynth I met several people who were working on similar systems, and I always tried to be positive, supportive and cooperative. I let the quality of my work speak for itself, and trusted people to judge its value for themselves.

I’ve never felt like I was the best inventor, programmer or researcher in the world, but even in 1997 I had a fair amount of experience and education in research and technology. I felt like those skills were being wasted when I was taking telephone messages at John Hancock, and even when I was reinstalling network drivers. Of course, there are a lot of highly skilled people out there, maybe more than there’s a need for.

After putting SignSynth on the shelf and focusing on French negation for my dissertation, I didn’t feel the same level of excitement; the theoretical advancements that my committee demanded felt small by comparison, although I’m still proud of them.

I have felt a bit more excitement for my recent work for the New School. It’s a more simple project, just retrieving class listings or final grades from the student information system and presenting it in a table, but it helps save time and effort for students and faculty. Less exciting, but still satisfying.