I was pleased to have the opportunity to announce some progress on my Digital Parisian Stage project in a lightning talk at the kickoff event for New York City Digital Humanities Week on Tuesday. One theme that was expressed by several other digital humanists that day was the sheer volume of interesting stuff being produced daily, and collected in our archives.

I was particularly struck by Micki McGee’s story of how working on the Yaddo archive challenged her commitment to “horizontality” – flattening hierarchies, moving beyond the “greats” and finding valuable work and stories beyond the canon. The archive was simply too big for her to give everyone the treatment they deserved. She talked about using digital tools to overcome that size, but still was frustrated in the end.

At the KeystoneDH conference this summer I found out about the work of Franco Moretti, who similarly uses digital tools to analyze large corpora. Moretti’s methods seem very useful, but on Tuesday we saw that a lot of people were simply not satisfied with “distant reading”:

Interesting trend I’m noticing at #nycdhweek: lots of admissions to working with data by hand alongside automated processes

— Shana Kimball (@shanakimball) February 9, 2016

Lot of talk abt hands on data work that needed b4 using dig tools. Are we training for that data knowledge & practice correctly? #NYCDHWeek

— Kimon Keramidas (@kimonizer) February 9, 2016

I am of the school that sees quantitative and qualitative methods as two ends of a continuum of tools, all of which are necessary for understanding the world. This is not even a humanities thing: from geologists with hammers to psychologists in clinics, all the sciences rely on close observation of small data sets.

My colleague in the NYU Computer Science Department, Adam Myers, uses the same approach to do natural language processing; I have worked with him on projects like this (PDF. We begin with a close reading of texts from the chosen corpus, then decide on a set of interesting patterns to annotate. As we annotate more and more texts, the patterns come into sharper focus, and eventually we use these annotations to train machine learning routines.

One question that arises with these methods is what to look at first. There is an assumption of uniformity in physics and chemistry, so that scientists can assume that one milliliter of ethyl alcohol will behave more or less like any other milliliter of ethyl alcohol under similar conditions. People are much less interchangeable, leading to problems like WEIRD bias in psychology. Groups of people and their conventions are even more complex, making it even more unlikely that the easiest texts or images to study are going to give us an accurate picture of the whole archive.

Fortunately, this is a solved problem. Pierre-Simon Laplace figured out in 1814 that he could get a reasonable estimate of the population of the French Empire by looking at a representative sample of its d?partements, and subsequent generations have improved on his sampling techniques.

We may not be able to analyze all the things, but if we study enough of them we may be able to get a good idea of what the rest are like. William Sealy “Student” Gosset developed his famous t-test precisely to avoid having to analyze all the things. His employers at the Guinness Brewery wanted to compare different strains of barley without testing every plant in the batch. The p-value told them whether they had sampled enough plants.

I share McGee’s appreciation of “horizontality” and looking beyond the greats, and in my Digital Parisian Stage corpus I achieved that horizontality with the methods developed by Laplace and Student. The creators of the FRANTEXT corpus chose its texts using the “principle of authority,” in essence just using the greats. For my corpus I built on the work of Charles Beaumont Wicks, taking a random sample from his list of all the plays performed in Paris between 1800 and 1815.

What I found was that characters in the randomly selected plays used a lot less of the conservative ne alone construction to negate sentences than characters in the FRANTEXT plays. This seems to be because the FRANTEXT plays focused mostly on aristocrats making long declamatory speeches, while the randomly selected plays also included characters who were servants, peasants, artisans and bourgeois, often in faster-moving dialogue. The characters from the lower classes tended to use much more of the ne ? pas construction, while the aristocrats tended to use ne alone.

Student’s t-test tells me that the difference I found in the relative frequency of ne alone in just four plays was big enough that I could be confident of finding the same pattern in other plays. Even so, I plan to produce the full one percent sample (31 plays) so that I can test for differences that might be smaller

It’s important for me to point out here that this kind of analysis still requires a fairly close reading of the text. Someone might say that I just haven’t come up with the right regular expression or parser, but at this point I don’t know of any automatic tools that can reliably distinguish the negation phenomena that interest me. I find that to really get an accurate picture of what’s going on I have to not only read several lines before and after each instance of negation, but in fact the entire play. Sampling reduces the number of times I have to do that reading, to bring the overall workload down to a reasonable level.

Okay, you may be saying, but I want to analyze all the things! Even a random sample isn’t good enough. Well, if you don’t have the time or the money to analyze all the things, a random sample can make the case for analyzing everything. For example, I found several instances of the pas alone construction, which is now common but was rare in the early nineteenth century. I also turned up the script for a pantomime about the death of Captain Cook that gave the original Hawaiian characters a surprising (given what little I knew about these attitudes) level of intelligence and agency.

If either of those findings intrigued you and made you want to work on the project, or fund it, or hire me, that illustrates another use of sampling. (You should also email me.) Sampling gives us a place to start outside of the “greats,” where we can find interesting information that may inspire others to get involved.

One final note: the first step to getting a representative sample is to have a catalog. You won’t be able to generalize to all the things until you have a list of all the things. This is why my Digital Parisian Stage project owes so much to Beaumont Wicks. This “paper and ink” humanist spent his life creating a list of every play performed in Paris in the nineteenth century – the catalog that I sampled for my corpus.

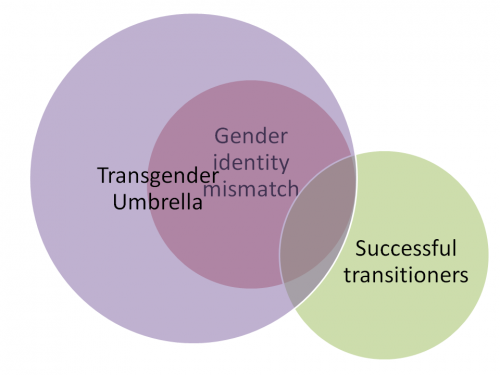

The original use of “transgender” was as an “umbrella” term including transvestites, transsexuals, drag queens, butch lesbians, genderqueer people and more. Another popular definition is based on “gender identity,” including

The original use of “transgender” was as an “umbrella” term including transvestites, transsexuals, drag queens, butch lesbians, genderqueer people and more. Another popular definition is based on “gender identity,” including