Data Science is all the rage these days. But this current craze focuses on a particular kind of data analysis. I conducted an informal poll as an icebreaker at a recent data science party, and most of the people I talked to said that it wasn’t data science if it didn’t include machine learning. Companies in all industries have been hiring “quants” to do statistical modeling. Even in the humanities, “distant reading” is a growing trend.

There has been a reaction to this, of course. Other humanists have argued for the continued value of close reading. Some companies have been hiring anthropologists and ethnographers. Academics, journalists and literary critics regularly write about the importance of nuance and empathy.

For years, my response to both types of arguments has been “we need both!” But this is not some timid search for a false balance or inclusion. We need both close examination and distributional analysis because the way we investigate the world depends on both, and both depend on each other.

I learned this from my advisor Melissa Axelrod, and a book she assigned me for an independent study on research methods. The Professional Stranger is a guide to ethnographic field methods, but also contains some commentary on the nature of scientific inquiry, and mixes its well-deserved criticism of quantitative social science with a frank acknowledgment of the interdependence of qualitative and quantitative methods. On Page 134 he discusses Labov’s famous study of /r/-dropping in New York City:

The catch, of course, is that he would never have known which variable to look at without the blood, sweat and tears of previous linguists who had worked with a few informants and identified problems in the linguistic structure of American English. All of which finally brings us to the point of this example traditional ethnography struggles mightily with the existence of pattern among the few.

Labov acknowledges these contributions in Chapter 2 of his 1966 book: Babbitt (1896), Thomas (1932, 1942, 1951), Kurath (1949, based on interviews by Guy S. Lowman), Hubbell (1950) and Bronstein (1962). His work would not be possible without theirs, and their work was incomplete until he developed a theoretical framework to place their analysis in, and tested that framework with distributional surveys.

We’ve all seen what happens when people try to use one of these methods without the other. Statistical methods that are not grounded in close examination of specific examples produce surveys that are meaningless to the people who take them and uninformative to scientists. Qualitative investigations that are not checked with rigorous distributional surveys produce unfounded, misleading generalizations. The worst of both worlds are quantitative surveys that are neither broadly grounded in ethnography nor applied to representative samples.

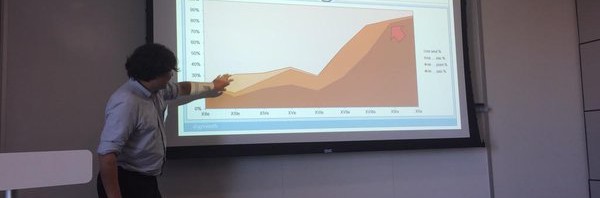

It’s also clear in Agar’s book that qualitative and quantitative are not a binary distinction, but rather two ends of a continuum. Research starts with informal observations about specific things (people, places, events) that give rise to open-ended questions. The answers to these questions then provoke more focused questions that are asked of a wider range of things, and so on.

The concepts of broad and narrow, general and specific, can be confusing here, because at the qualitative, close or ethnographic end of the spectrum the questions are broad and general but asked about a narrow, specific set of subjects. At the quantitative, distant or distributional end of the spectrum the questions are narrow and specific, but asked of a broad, general range of subjects. Agar uses a “funnel” metaphor to model how the questions narrow during this progression, but he could just as easily have used a showerhead to model how the subjects broaden at the same time.

The progression is not one-way, either. The findings of a broad survey can raise new questions, which can only be answered by a new round of investigation, again beginning with qualitative examination on a small scale and possibly proceeding to another broad survey. This is one of the cycles that increase our knowledge.

Rather than the funnel metaphor, I prefer a metaphor based on seeing. Recently I’ve been re-reading The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and in Chapter 8 Michael Pollan talks about taking a close view of a field of grass:

In fact, the first time I met Salatin he’d insisted that even before I met any of his animals, i get down on my belly in this very pasture to make the acquaintance of the less charismatic species his farm was nurturing that, in turn, were nurturing his farm.

Pollan then gets up from the grass to take a broader view of the pasture, but later bends down again to focus on individual cows and plants. He does this metaphorically throughout the book, as many great authors do: focusing in on a specific case, then zooming out to discuss how that case fits in with the bigger picture. Whether he’s talking about factory-farmed Steer 534, or Budger the grass-fed cow, or even the thousands of organic chickens that are functionally nameless under the generic name of “Rosie,” he dives into specific details about the animals, then follows up by reporting statistics about these farming methods and the animals they raise.

The bottom line is that we need studies from all over the qualitative-quantitative spectrum. They build on each other, forming a cycle of knowledge. We need to fund them all, to hire people to do them all, and to promote and publish them all. If you do it right, the plural of anecdote is indeed data, and you can’t have data without anecdotes.